Content

All CAS Inquire talks will be in the Jackie Gaughan Multicultural Center, Ubuntu Room/202, 5:00 - 6:00 p.m.

“Navigating Uncertainty in Climate Projections: Scenarios, Simulations, and Earth's Complexity”

We live in a changing world. In the past 100 years, the Earth’s surface air temperature increased an average of 0.6° Celsius (1.1°F) due to an increase in atmospheric greenhouse gases produced by burning fossil fuels. While this may not seem like very much, a global change of this magnitude has significant local impacts on human health and well-being. Further anthropogenic climate change will impact the world’s water in profound and complex ways, including amplifying both water scarcity and hazards associated with water.

It is essential to have reliable regional climate projections for understanding, quantifying, and communicating these risks, as well as developing adequate responses and mitigation strategies to reduce these risks. However, there is uncertainty in projections of regional climate, especially with regard to precipitation.

This uncertainty stems from three main sources:

- future emissions scenarios (human behavior)

- representing the complexity of the Earth system numerically (model uncertainty)

- natural variations in the climate system (internal variability)

My research seeks to disentangle these sources of uncertainty in regional climate projections and reduce uncertainty through improving models and providing guidance to stakeholders for how to use climate projections. To further this research, I regularly design and run numerical simulations, apply statistical techniques to model output and observational data, and collaborate with researchers who study climate impacts.

In this talk, I will explore these ideas by performing live climate simulations with a simple climate model and show how sensitive the simulations are to emissions scenarios and how the model represents climate feedbacks. In this way we can explore how a climate model works, why we should trust them, and how we can use them to understand Earth’s future climate.

“Haunted: Uncertainty, Insecurity, and Fear of Crime”

“I didn’t ask you whether you believe that ghosts are seen, but whether you believe that they exist.” Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment

This lecture explores how social uncertainty shapes knowledge, decision-making, and the human condition, emphasizing how attitudes about crime and punishment are ways people translate the unknown into the “known.”

In the study of public attitudes about crime, criminal justice, and related issues (e.g., immigration regulations, illicit drug use, homelessness), we often confront questions about why the evidence-based “reality” of the issue does not match public perceptions. For example, if crime is objectively down based on available statistics, why do people routinely tend to think it is up? Here, researchers often examine how information is accessed by users and how it is presented in ways that distort reality. Furthermore, in the study of attitudes, we confront the question of how the public’s (mis)perceptions may influence preferences for restrictive or punitive policies. If people think crime is up (even if it is not), they may express greater support for building prisons, for instance. This is an instrumental response: dealing with a perceived problem by using known tools.

Preferences for punitive policy, research shows, are about much more than knowledge – they are also about feelings. Attitudes about crime and crime policies are expressive: Expressive of anger, of fear, of uncertainty. The expressive nature of attitudes about crime can be understood not only as dissatisfaction with current situations but also as a nostalgic response (1). Dramatic social changes spur glossy recollections of “safer” or “better” times. Yet as a society, we are also haunted by the failures of the past that linger on the edges of both nostalgia and uncertainty (2). For example, “crackdowns” on crime excite the public, politicians, and the media, but ultimately fail, leaving behind people, unnamed cultural scars, and seemingly intractable social ills. Likewise, the systems designated to deal with social problems appear increasingly untrustworthy. Indeed, research has documented a steady increase in public distrust.

Collectively, such subjective perceptions reflect ontological insecurity (3). A sense of “existential precariousness” and anxiety about the future – for both self and society – generates a sense of insecurity beyond specific instrumental worries about crime and safety. Perceived personal vulnerability, economic or political uneasiness, and broad social insecurity find expression in fears about something that seems more tangible – crime. Punitiveness may be understood as a retreat to the status quo, doubling-down on the known to alleviate discomfort with the unknown. In an historic moment of distrust, widespread uncertainty about the present and future, manipulation of the past, and politization of the “other,” we might ask ourselves, “What happens when we believe in ghosts?”

1. Farrall, S., Gray, E., & Jones, P. M. (2021). Worrying times: the fear of crime and nostalgia. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 33, 340-358.

2. Simpson, A., Lee, M., & McGuinness, P. (2024). ‘I’ve seen people on the train, like really weird people.’ Hauntological reflections on the fear of crime. Crime, Media, Culture, doi.org/10.1177/17416590241290453

3. Valente, R., & Pertegas, S. V. (2018). Ontological insecurity and subjective feelings of unsafety: Analyzing socially constructed fears in Italy. Social Science Research, 71, 160-170.

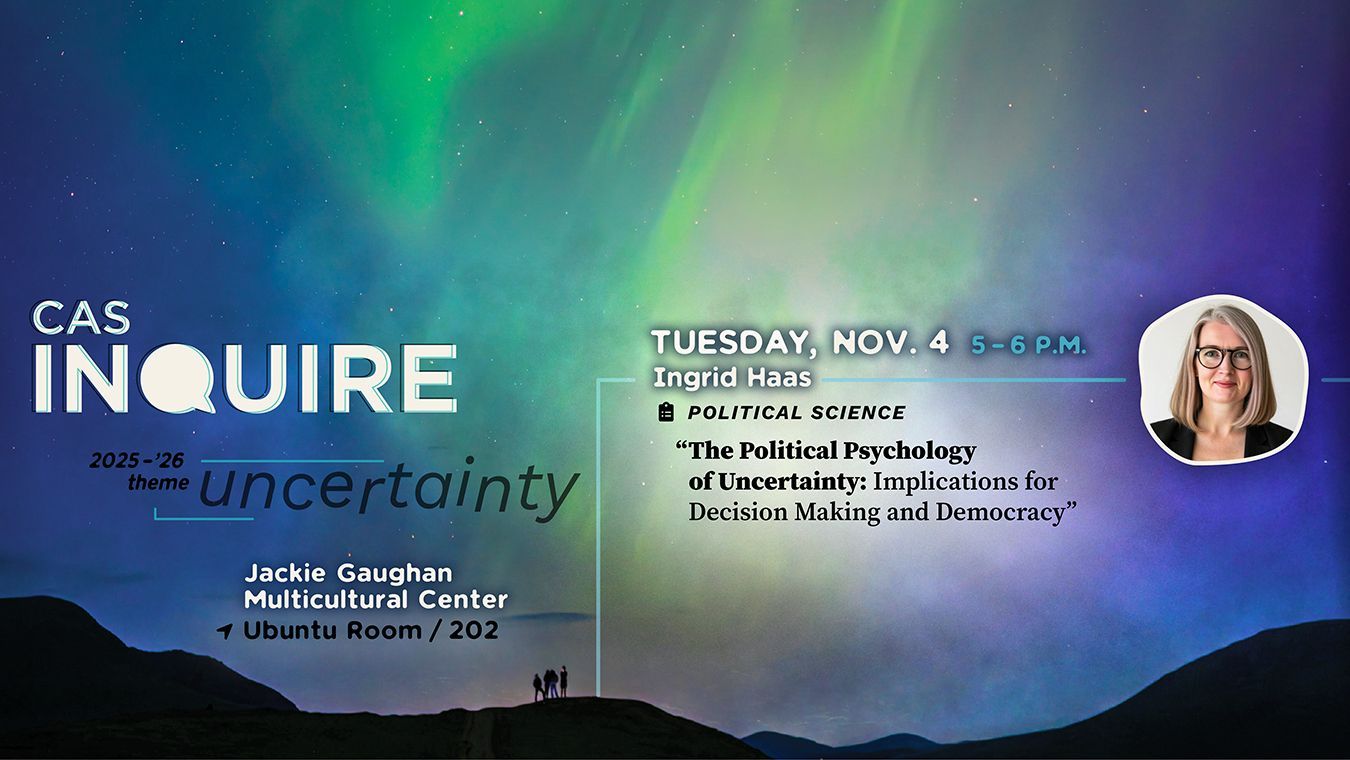

“The Political Psychology of Uncertainty: Implications for Decision Making and Democracy”

Living with uncertainty is a fundamental part of the human condition, yet we still don’t always understand how uncertainty will impact decision making and behavior. Our work suggests that responses to uncertainty are context-dependent, suggesting that the way in which the uncertainty is interpreted can lead to different outcomes1. More specifically, uncertainty can be attached to positive information, where it can increase open-mindedness and cognitive flexibility, or uncertainty can be attached to feelings of threat, where it is more likely to have the opposite effect—closing people off to new information.

In our work, we explore the implications of uncertainty for political cognition and decision making, examining outcomes like political tolerance and support for compromise, and considering implications of uncertainty for support of democratic norms more broadly. We also investigate the neural underpinnings of cognitive response to uncertainty and implications for political cognition2.

In this talk, I would give a psychological overview of uncertainty, discuss implications for social and political cognition, and think about implications for contemporary American democracy.

1. e.g., Haas & Cunningham, 2014; Haas, 2016

2. e.g., Haas, Baker, & Gonzalez, 2021

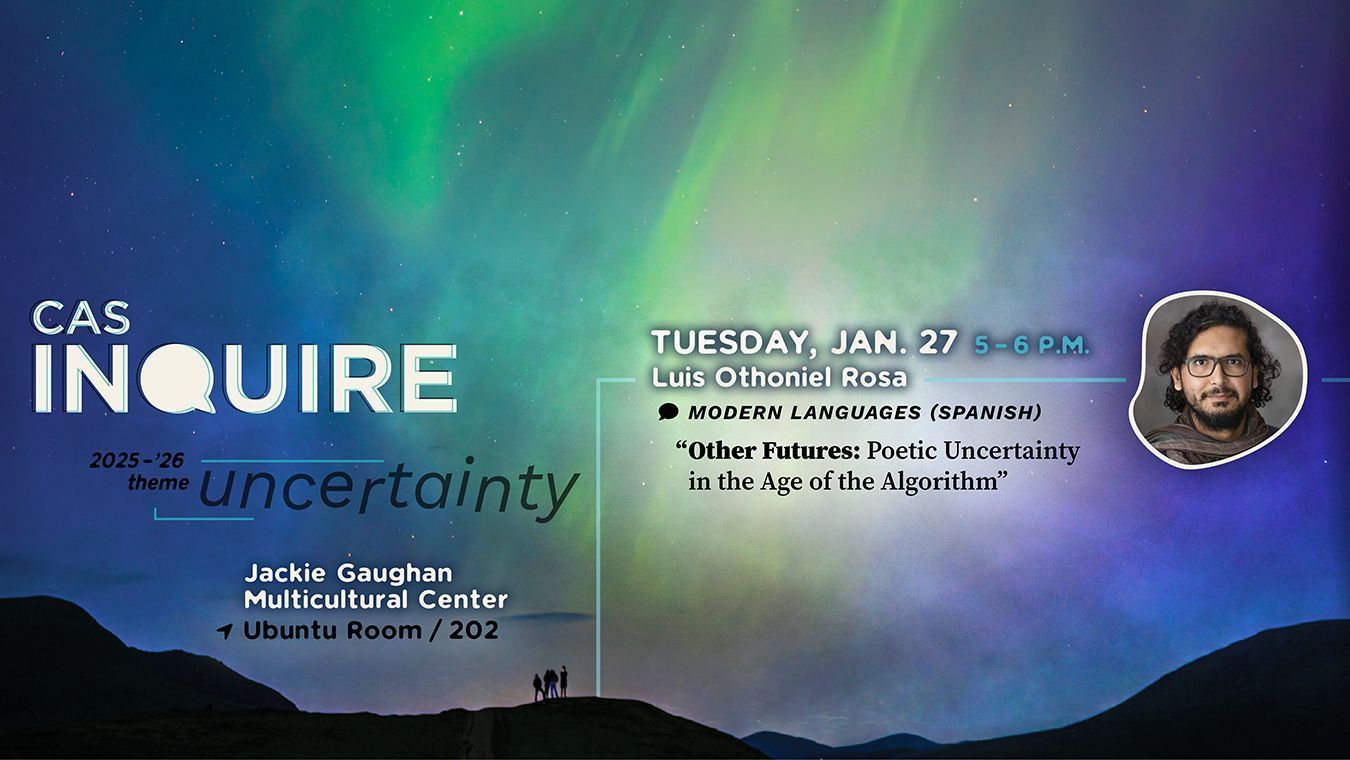

“Other Futures: Poetic Uncertainty in the Age of the Algorithm”

Poetry is confusing. And that is its purpose.

As emerging language technologies codify the universe into signs and life into abstractions, an ironclad logic seems to determine our reality and to cripple our ability to think (and then construct) other possible futures. Our present and future seems to be determined, written in stone, and statistically predestined toward catastrophes (ecological, demographic, military, economic, etc.).

In this context, we argue, poetic language emerges to open a crack into this logic; by confusing the algorithms that seem to determine our reality, poetics conjures other possible realities that expand and multiply our horizons of possibility.

- We will start with the first poem in human history, written more than 4,000 years ago, the "Song of Inanna" by the Sumerian priestess, Enheduanna, written in the same culture that invented the technology of writing (which coincides with the invention of enslavement).

- We will continue with a poet who, from a within a colony of the US empire, in the 1970’s, wrote about an “Animal” with collective consciousness, the Afro-Puerto Rican poet Ángela María Dávila, translated into English for the first time last year by trans poet Roque Raquel Salas Rivera.

- We will end with a discussion of the “hologram” of an Indigenous revolutionary character in the present, the pan-Mayan fictional character in the south of Mexico, Subcomandante Marcos, in the same culture that gave us the most sophisticated mathematical understanding of time and calendars, and in a geopolitical space (Chiapas) that embodies the most violent and deadly aspects of capitalism today.

Through these examples, we will establish poetry’s insurgency against the technological determinacy of power and how poetic language helps us to transform the present technologies of domination into technologies of liberation. In our discussion, we will pay particular attention to current debates about artificial intelligence, the “physics of consciousness” (Sir Roger Penrose), Black and Indigenous futurisms, and ways of nurturing our technologies for the reproduction of life, rather than for the productivism of capital. Through poetic uncertainty, we are creating new mythologies for a future society that our systems of power deem impossible.

“Holy Agnosticism”

Many are certain about who God is and what God says. They tend to gather together in groups of like-minded people, sometimes regarding people who lack their certainty poorly. Lacking certainty about a divine being is perceived as being “weak in faith” or “unwilling to commit to a religious position.” Many who admit that they cannot commit to certainty about God call themselves “agnostic.”

But agnosticism is not simply admitting ignorance about divinity. Indeed, there are many highly regarded figures in religious traditions who have developed sophisticated, fulfilling spiritual lives, even writing texts that have inspired millions all over the world, who have struggled with certainty about God. The word “agnostic” comes from the Greek gnosis, which means “knowledge.” Someone who is “agnostic” is someone without knowledge, in this case, about divinity. But absence of knowledge is not necessarily absence of experience.

Most people have had experiences that have been real, important, but ambiguous. “What was THAT all about?” is the normal question that follows. Usually, these experiences are with other people. But in some cases, people have such experiences alone. They have been troubled, despondent, or even enraged, but have experienced something that defies all explanation. They have encountered another being, another presence, that somehow reaches into their being. Such people, if they are lucky, are able to talk with others about such an encounter, to write about them, to gain insight into them. They even learn to embrace their profound absence of understanding of the other they have encountered.

The sacred texts of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam have stories of many who have had such experiences, telling of ordinary people who at one point encounter what they later realize to be divinity, whose lives are irrevocably changed. They have been called prophets, visionaries, saints, and holy teachers. The written records they leave behind record struggles with their encounters, in some cases suffering because of what they have felt compelled to say.

Less than a century ago, a word was invented to describe these encounters: Mysticism. While the word seems to describe something unearthed from antiquity, it was only coined when scholars invented a new science, the study of religion. The Mystic, for such thinkers, was the inexplicable experience people describe of encountering the source of all meaning in reality in the darkness of doubt. They describe an overpowering loss of their sense of self, and its need for certainty, in what one called “Learned Ignorance.”

This lecture will introduce this two thousand year old tradition of the embrace of Not Knowing God that is Western Mysticism.